What is a HAB?

The Good, The Bad, The Blooming Ugly

If you’ve ever seen slimy green water and thought, “Yikes, what happened here?” — chances are, you’ve met a HAB.

Harmful Algal Blooms, or HABs (you’ll see that word a lot around here!), happen when colonies of algae, those simple plant-like organisms that live in both freshwater and saltwater, grow out of control and release toxins that harm people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds. The human illnesses caused by HABs, though rare, can be debilitating and sometimes even fatal (NOAA, 2016).

And while they sound like full-time villains, algae aren’t bad by nature. In fact, they’re quite beneficial for the water world — until they’re not.

Under normal conditions, algae form the foundation of aquatic life, producing 30–50% of Earth’s oxygen and feeding nearly everything that swims, crawls, or floats. Without them, we’d be in serious trouble.

They’ve been a part of East Asian diets for centuries, used in food, medicine, cosmetics, and even as biofuel – an alternative to fossil fuels. It’s only when conditions favor their rapid growth that they turn from ecological allies into environmental troublemakers.

Figure 1: Algae powder intended for human consumption

Like the saying goes, “Too much of anything is bad.” Similarly, when temperatures and nutrient levels are high, algal cell counts grow out of proportion becoming harmful. They use up the oxygen in the water, poisoning aquatic animals and waterfowl (Britannica, 2019).

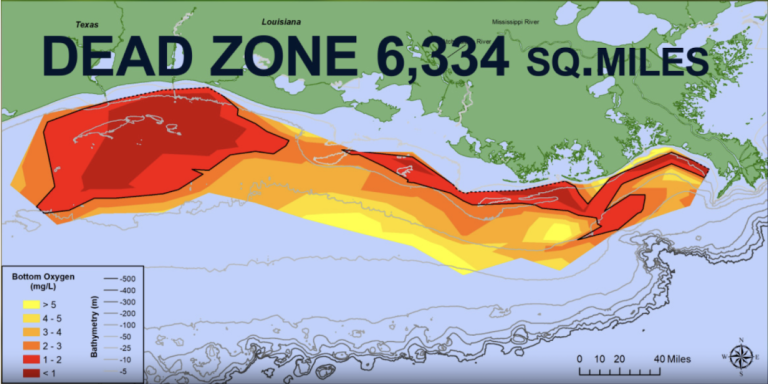

It gets worse. When a HAB dies i.e decomposes they consume oxygen faster than it can be replaced. Oxygen levels drop to the point where the water body can no longer support aquatic life. The water becomes corrosive, discolored, and may contain manganese, which is a toxic metal deadly to humans at high levels (Harmful Algal Blooms & Hypoxia, n.d.). This water body becomes what is known as a dead zone or a more technical term: hypoxia. More than 165 dead zones have been documented nationwide, affecting major water bodies like the Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Mexico (US EPA, 2019).

Once a bloom reaches this stage, there’s no turning back. It’s now about damage control not recovery.

Just in 2022 alone, there were 375 HABs recorded across the United States (CDC, 2024), with each HAB costing affected regions thousands to millions of dollars. Fisheries close, tourists cancel trips, and local communities suffer.

Figure 3: A NOAA scientist collecting water samples in Lake Erie to help forecast and monitor a HAB

The truth is, once a HAB forms, there’s not much we can do. Cleanup is expensive, unpredictable, and often too late.

That’s why early detection is key. By monitoring nutrient levels, temperature spikes, and algal cell counts, scientists can spot blooms before they explode and stop them in their tracks.

With HABs, we can’t just react. We need to prevent the problem, not diagnose it.

Now that we’ve covered what a HAB is and why it matters, the next question is:

Which algae cause the most damage?

In an upcoming article, we’ll explore the Top 2 HABs that impact 90% of the U.S., where they occur, and the damage they’ve done.

Stay tuned!

References:

- (Britannica, 2019)

Britannica. (2019). Algae – Ecological and commercial importance. In Encyclopedia Britannica.https://www.britannica.com/science/algae/Ecological-and-commercial-importance - (CDC, 2024)

CDC. (2024). Summary report – One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System (OHHABS), United States, 2022. One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System (OHHABS). https://www.cdc.gov/ohhabs/data/summary-report-united-states-2022.html - (Harmful Algal Blooms & Hypoxia, n.d.)

Harmful algal blooms & hypoxia pose a risk to drinking water quality for millions of Great. (n.d.). https://ciglr.seas.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/HABs-Hypoxia-Fact-Sheet.pdf - (NOAA, 2016)

NOAA. (2016, April 27). What is a harmful algal bloom? Noaa.gov. https://www.noaa.gov/what-is-harmful-algal-bloom - (US EPA, 2019)

US EPA. (2019, April 18). The effects: Environment | US EPA. US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/effects-environment